Touching base.

I have not forgotten you

It has been a long time since I published a chapter. The reason for that is the Sheepskin Volume 2 draft was in much rougher shape than I thought. It has needed a lot more edits, revisions, and careful attention than the first volume. I decided it was more important to absolutely stick the landing on this sequel, and that required focusing on it as a complete novel rather than as a serial. When the chapters are ready, you will get an opportunity to read them ahead of time prior to the release of the novel on Amazon.

Earlier this year, Sheepskin Volume 1 was included in the “Summer 2025 Based Book Sale” organized by Hans G. Schantz and saw good success there, although the social media push for that took up time I would have rather spent writing.

For the foreseeable future, I have outsourced book marketing and greatly reduced my social media presence to allow me to focus on finishing Volume 2.

At the advice of a friend, I am also developing a nonfiction series, Baneful Banality, spotlighting the everyday evil forces that inspired me to write the Sheepskin series in the first place. It will also delve into one of my favorite topics: post-mortem examinations of disasters brought about by human error.

In the works is also an audio version of A Small Price. More Tales From Hammersmith Valley are coming as soon as I think of some.

To inaugurate Baneful Banality, I will finish this update out by sharing a piece I wrote some time ago on one of the most fascinating and impactful tragedies in modern history: the R.M.S. Titanic. Below is a brief biography of one of the Titanic tragedy’s most towering figures, a man who worked hard, loved deeply, and saw his life cut short by the compounding of other men’s mistakes and hubris.

Thank you for hanging in there with me, and I will be bringing you more content soon.

JTP

“I am just now learning the Titanic was a real ship.” This admission exploded across social media in the immediate wake of the unfortunate OceanGate tragedy. It’s a sad reminder that we are doomed to repeat the history we refuse to learn. Fortunately, the history of the Titanic, both before and after the sinking, is fascinating.

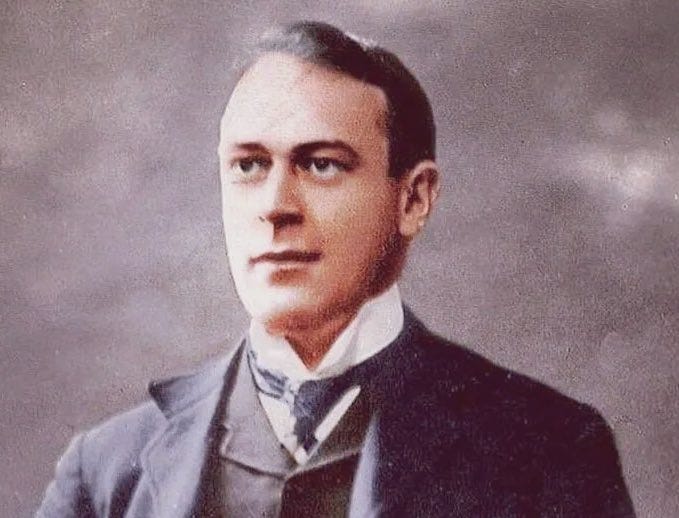

And no discussion of the Titanic’s history would be complete without first examining the life and death of arguably its most tragic figure: Thomas Andrews, managing director and head of drafting at the Harland & Wolff shipbuilding company.

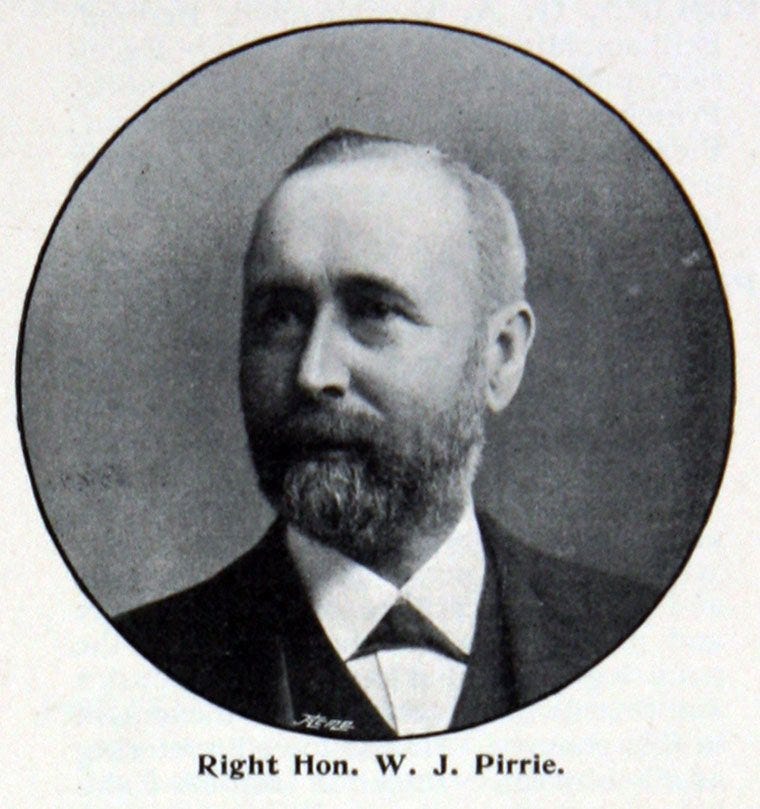

Thomas Andrews was born in Comber, Ireland, on February 7th, 1873. The Andrews family was prominent in Ireland; his father and two brothers were politicians. Thomas’s maternal uncle was William Pirrie, Harland & Wolff’s chairman.

Everyone who met Andrews loved him: children, elders, animals. He was described by his family after the disaster as an inquisitive and temperate lad full of vitality and compassion for every living thing around him. He was particularly talented at cricket and horsemanship. He developed an interest in boats by the time he was eleven years old. He was not very interested in school, but he would stop at the shipyard on the way home and listen to the sounds of hammers.

At the age of sixteen, Andrews was placed in a premium apprenticeship at Harland & Wolff. Did his relationship to Lord Pirrie play a role? Possibly. But Pirrie made it clear to his employees that the boy was to be treated as any other apprentice and given no special favor.

One thing is for certain, though: Andrews did not waste the opportunity. He busted his ass at that apprenticeship. Here is an excerpt from the biography Thomas Andrews, Shipbuilder:

“But Tom was not of the breed that fails. He took to his work instantly and with enthusiasm. Distance from home necessitated his living through the workaday week in Belfast. Every morning he rose at ten minutes to five and was at work in the Yard punctually by six o’clock. His first three months were spent in the Joiner’s shop, the next month with the Cabinet makers, the two following months working in ships. There followed two months in the Main store; then five with the Shipwrights, two in the Moulding loft, two with the Painters, eight with the iron Shipwrights, six with the Fitters, three with the Pattern-makers, eight with the Smiths. A long spell of eighteen months in the Drawing office completed his term of five years as an apprentice.”

He took extra shifts to fill in for sick workers, repaired leaking holds, and memorized every detail of the shipbuilding process. That alone would be exhausting to most, but he also stayed up until eleven PM most nights, studying naval theory, and he played cricket once a week.

In 1894, at the age of twenty-one, Andrews was hired to the drawing office of Harland & Wolff. He rose quickly to the top, supervising constructions, repairs, and modifications. He was always a physical presence in the yard, walking among the workers. More than once, he nearly got killed by dropped rivets and stray tools. He would catch slackers and give them a talking to; everyone got exactly one chance to get it together. He would jump in and help out with any problem he saw.

The contemporaries of Thomas Andrews said he could have built a ship from the ground up, riveted it, driven its engine, steered and captained it on his own. He knew everything a man could know about ships.

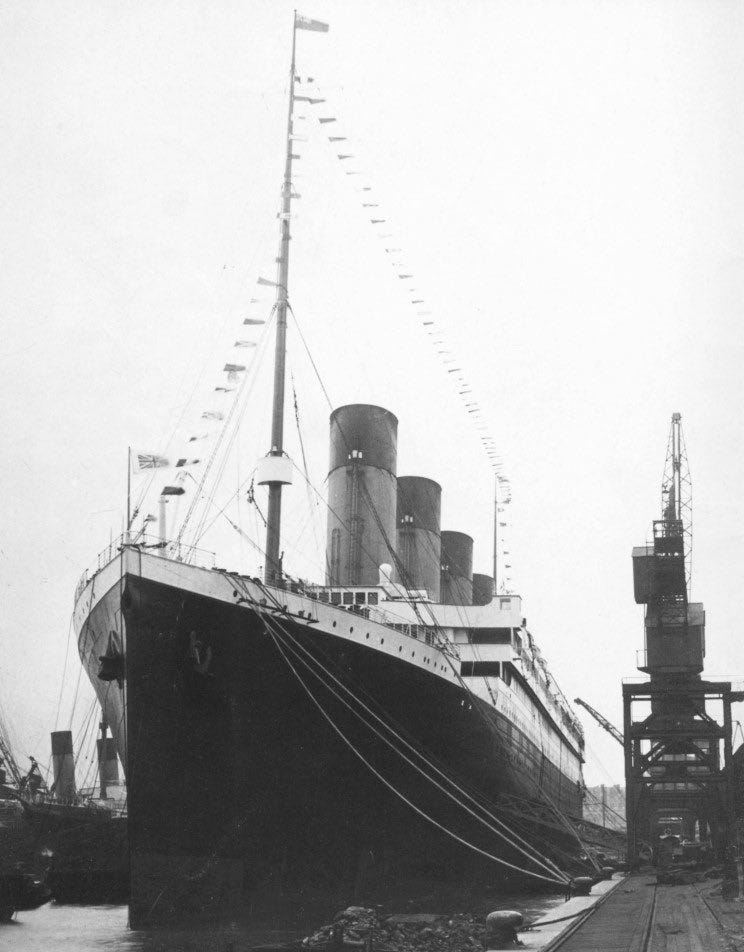

In 1907, plans began for three new Olympic-class liners for the White Star Line. These ships—the Olympic, the Titanic, and the Britannic—were designed to be the biggest and safest ocean liners ever built.

Andrews famously asked for forty-eight lifeboats per ship, rather than twenty, and was overruled.

But what is not so widely discussed is that Harland & Wolff’s leaders, including Lord Pirrie, were following the convention of the time with that decision. The purpose of the lifeboats was not to have capacity for every passenger at once, but to ferry them to the safety of a rescuing ship.

(All other factors being equal, forty-eight lifeboats may not have helped, as the crew of the Titanic only managed to launch eighteen of the twenty it did have on hand.)

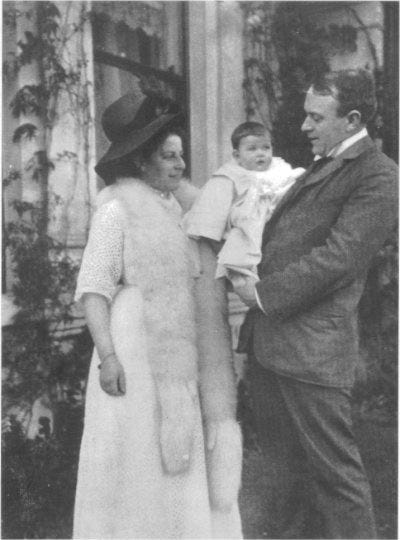

In 1908, Thomas Andrews married Helen Reilly Barbour, and in 1910, they had a daughter, Elizabeth Law Barbour Andrews. Shortly before Elizabeth was born, Andrews took his pregnant wife to view the Titanic under construction at the shipyard.

The Titanic left Belfast on April 2nd, 1912. Andrews was on board and supervised every aspect of her operation, making notes and conducting inspections on behalf of his employer. He was extremely busy during the days the Titanic spent at the Southampton dock.

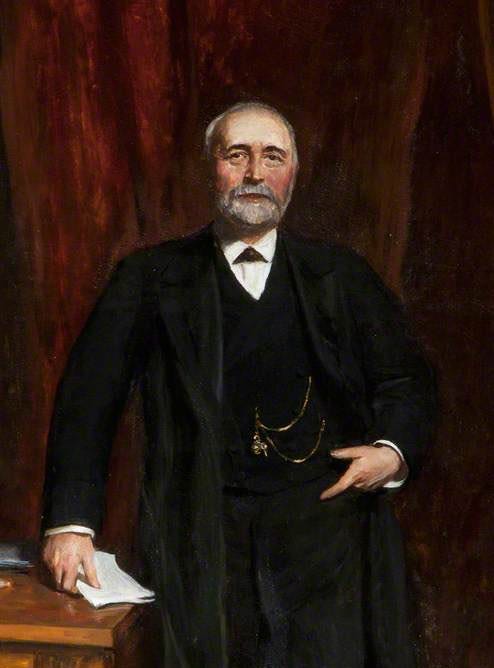

Lord Pirrie, by the way, was a business associate and close friend of J. Bruce Ismay and other prominent members of the White Star Line. Pirrie was intended to be on the Titanic’s maiden voyage, but he was recovering from surgery and sent Andrews in his place.

The news of Thomas Andrews’s death devastated Lord Pirrie, who was still in recovery on top of that personal loss. He was not asked to testify in the investigation afterward because of his condition.

The lifeboat decision would torment Pirrie until his death from pneumonia ten years later.

As I mentioned, the Titanic’s crew did not even get to launch the lifeboats they had. The two collapsibles simply floated off. If the crew had taken any longer to realize the ship was sinking and take action, more lives would have been lost that night. The singular attention to detail and dedication to the craft shown by Thomas Andrews is rightfully credited with saving lives.

Victor Garber was a great choice to play Andrews in the James Cameron film, but the dramatic scene of him being last seen in the smoking room staring at the clock may have been inaccurate. Multiple eyewitnesses reported seeing him on deck after that time, throwing chairs to people treading water in the frigid North Atlantic.

Other reports said he was ultimately at the bridge with Captain Edward Smith at the end.

The lessons learned from the Titanic were later applied to make her younger sister, the R.M.S. Britannic, even more robust. She was put into service as a hospital ship during World War I. She unfortunately struck a mine and sank in the Aegean Sea in 1916.

The Britannic sank even faster than the Titanic, but thirty-five of her forty-eight lifeboats were launched, saving 1,036 of her 1,066 passengers that day. Add that to the number of wounded people treated on that ship, and the Britannic likely saved more lives in total than were lost on the Titanic.

I like to think that this fact would give Thomas Andrews some peace.

“A Queen’s Island Trojan, he worked to the last;

Very proud we all feel of him here in Belfast;

Our working-men knew him as one of the best—

He stuck to his duty, and God gave him rest.”

Good to see it!